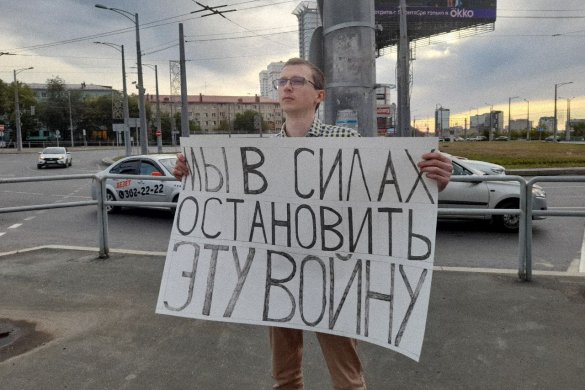

Illustration: OVD-Info

Persecution of the anti-war movement report: Three Years into Russia’s Full-Scale Invasion of Ukraine. February 2025

Introduction

The third year of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine continues to be marked by ongoing political repression within the country. Despite a decline in large-scale anti-war protest, tight censorship and pressure on civil society — including on activists, journalists and NGOs — remains unrelenting. The authorities continue to deploy the full range of repressive measures — from criminal prosecutions for spreading «fakes» about the Russian army and charges of «discrediting» the armed forces to extrajudicial punishments, including dismissals from work, family intimidation and denial to issue official documents. New laws are also being passed to expand the powers of the law enforcement officers and increase their ability to control dissent.

The Russian government places particular emphasis on suppressing anti-war sentiment online. Most criminal cases are initiated over social media posts, often targeting content published years before the prosecution begins. The practice of declaring independent media outlets, human rights organisations and individual activists «foreign agents» and «undesirable organisations» remains in effect. Meanwhile, new restrictions on the use of VPNs and widespread website blockages further limit access to independent information.

Law enforcement officers are not only targeting Russian citizens, but also Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilians from the occupied territories. Many of them face charges of espionage, terrorism or treason, leading to lengthy prison terms.

This report highlights the key trends in anti-war political repression in Russia by analysing changes in the legislation, mechanisms of pressure, as well as statistics on criminal and administrative cases. It also examines extrajudicial persecution as well as pressure on journalists and independent media, «foreign agents» and «undesirable organisations».

Detentions for Anti-War Stance

detentions for anti-war stance

According to OVD-Info data from 24 February 2022 to 17 February 2025.

Law enforcement officers began detaining individuals for expressing their anti-war views from the very first day of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, as Russians took to the streets in large-scale protests. In total we have documented over 18,900 arrests (excluding arrests made as part of criminal investigations) during public anti-war demonstrations in 2022. Throughout this period, Russians participated in several large rallies to voice their opposition to the ongoing military actions in Ukraine. Law enforcement frequently used force during arrests, as they had during previous mass protests.

After the introduction of laws in March 2022 criminalising the «discreditation» of the Russian military and spreading «fakes» about it (discussed in more detail below), which effectively banned any criticism of the invasion of Ukraine, people gradually stopped participating in large-scale anti-war protests. The last significant rallies took place in September 2022, when protests against mobilisation erupted in various regions of the country. After that, mass anti-war rallies once again began to fade. Russians increasingly expressed their dissent at smaller-scale events, often solitary pickets.

This trend is directly reflected in the declining number of arrests for anti-war activity: in 2023, there were 274 arrests related to public protest, while in 2024, this number dropped to 41. However, some Russians were detained multiple times, such as 79-year-old St. Petersburg artist Elena Osipova, who repeatedly took part in solitary pickets against the war. In certain cases, activists face additional pressure following their arrests. For instance, at the end of 2023, officers from the «Centre E» (Centre for Combating Extremism) detained Dmitry Kuzmin, who had been expelled twice from university for his anti-war stance, and attempted to serve him with a military draft notice at the police station.

Furthermore, over the three years of the war, law enforcement officers have detained individuals 856 times for anti-war posts, symbols and other actions that could be directly or indirectly linked to the war. This category includes not only posts openly criticising the war in Ukraine but also items that may not have been intended as political statements, such as a blue-yellow patch on a backpack. By the end of 2024, the majority of arrests for non-protest related activities were linked to social media posts.

Number of detentions for anti-war stance decreases

In 2024 and 2025, we recorded a total of 82 arrests, the majority of which took place in Moscow (27 instances) and St. Petersburg (13 instances). This is likely due to the fact that anti-war protests are more frequent in these cities than in other regions. Another eight arrests happened in Sverdlovsk Oblast, all related to solitary pickets.

Law enforcement officers also repeatedly detained residents of Tatarstan, Nizhny Novgorod, Novosibirsk and Bryansk Oblasts, Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug, Krasnodar, Krasnoyarsk and Khabarovsk Krais. In an additional 13 regions and the annexed Crimea, there were instances of people detained at least once.

Map of detentions for anti-war stance in 2024-2025

It is important to note that not all anti-war protests lead to arrests. Independent media outlets have repeatedly published photos of art installations that implicitly criticise the war. These images often appear online after the installations have been set up, making it often impossible to identify the authors.

In addition to anti-war activists, law enforcement officers also detained individuals who do not voice their opposition to the invasion of Ukraine itself but criticise specific government decisions related to the war. Notably, there were 46 arrests at events organised by the wives of mobilised Russian men, demanding the return of their husbands — Russians drafted during the fall 2022 mobilisation campaign cannot return home until the mobilisation decree expires. These arrests occurred in three cities: Moscow (40 instances), Yekaterinburg (five instances), and St. Petersburg (one instance).

The majority of detentions during these protests took place in February 2024. For example, at the beginning of the month, a protest against mobilisation organised by the «Put’ Domoy» («Path Home») movement was held near the Moscow Kremlin. The police detained 19 people. A week later, law enforcement officers detained five more people near the «Chernyy Tyulpan» («Black Tulip») memorial in Yekaterinburg.

Another relatively large protest leading to arrests took place in front of the Ministry of Defence building in September 2024. This rally was organised by a similar group of relatives of mobilised soldiers, «Belyye Platki» («White Scarves»). During the protest, the police detained 12 women who had stayed overnight at the ministry’s walls.

Number of detentions at protests organised by wives of mobilized soldiers in 2024

During the protests, the police detained not only relatives of the mobilised people, but also journalists who covered their protests. In particular, correspondents of RusNews and SOTAvision fell into the hands of law enforcement officers.

Criminal cases

The share of prosecutions for anti-war stance in all political prosecutions is decreasing

As of 17 February 2025, we are aware of 1,185 people facing criminal prosecution for anti-war statements or actions. At least 325 defendants have been prosecuted since February 2024. Right now, 913 people are facing «anti-war» criminal prosecution. These people include both those whose cases are being investigated or tried in court, as well as those who continue to serve their sentences. 372 of these people are in places of imprisonment.

The share of those who began facing prosecution in «anti-war» criminal cases in 2022 or 2023 was more than half of the total number of defendants in politically motivated criminal cases. In 2022 they were 57%, in 2023 — 53%.

In 2024, the share of «anti-war» defendants decreased significantly, amounting to 32% of all those prosecuted in politically motivated criminal cases.

We do not know exactly what is causing this decline, but we can make some conjectures. First of all, this may mean that there are fewer anti-war statements and actions themselves. Some may have been influenced by the news of harsh punishments for anti-war statements (for example, numerous court sentences ranging from five to eight and a half years under the «fake news» article), which has led to increased levels of self-censorship in society.

In addition, as we noted in the report on political persecution in 2024, law enforcement officers began to increasingly persecute people because of their status — both inherent (sexual orientation, foreign citizenship) and assigned (the «foreign agent» label or a connection with an «undesirable» or «extremist» organisation). Perhaps pursuing such cases requires less effort than prosecuting people for anti-war statements on social networks. Part of the role in reducing the share of «anti-war» persecutions was played by a mass case unrelated to the war — the one against participants of the popular gathering in Baymak (Bashkortostan) — which was initiated in early 2024.

This also applies to prosecutions under articles that were in fact enacted specifically to prosecute people with an anti-war position, such as the articles on spreading «fakes» about the Russian Armed Forces (Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code) or on discrediting the Russian army (Article 280.3 of the Criminal Code). For example, we do not consider as «anti-war» the prosecution of Ukrainian public figures against whom cases of «fakes» were brought, or residents of a village in Transbaikalia who attacked a fellow countryman who returned from the war and were charged with discrediting the army for that.

Analysing charges brought under articles not directly related to the war becomes even more difficult in this context.

Finally, it is worth to separately mention a group of politically motivated prosecutions that are related to the war in Ukraine, but they cannot be classified as «anti-war» (here and further they will be designated as «others war-related», although in some cases we can only assume the existence of this connection).

We describe these prosecutions in greater detail in a separate section. Here we will say that in 2022 the share of people subjected to such prosecutions was 14% of all persons involved in politically motivated prosecutions, 10% in 2023 and 9% in 2024. Thus, even taking these prosecutions into account, the proportion of war-related prosecutions has been declining year on year.

Number of defendants in criminal anti-war cases in Russian regions per 100 thousand population

Since 2022, we have recorded the highest number of «anti-war» prosecutions (against no less than 185 people) in Moscow. The second place is occupied by St. Petersburg with 87 prosecuted individuals, followed by the Sverdlovsk region (35 people), Tatarstan (34), the Moscow region (32), the annexed Crimea and the Krasnodar region (31 people each).

In some of these regions, the number of initiated cases has decreased year after year. On the other hand, in the Sverdlovsk region, the number of people facing prosecution in 2023 increased compared to 2022 (from 10 to 15), but fell again in 2024 (to 9 people). We see similar dynamics in the Krasnodar region (11 people in 2022, 14 in 2023 and 6 in 2024), while in the Moscow region the number of defendants has been growing steadily (8 in 2022, 10 in 2023 and 12 in 2024).

Articles

Rating of criminal articles by year when prosecution started

Among the articles under which «anti-war» criminal cases are initiated, the article on spreading knowingly false information (or, as it has come to be called in the media and on social networks, «fakes») about the Armed Forces stands out — Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code. It was hastily included in the Criminal Code in March 2022, shortly after the start of the full-scale invasion. Article 207.3 imposes punishment primarily for statements about crimes committed by the Russian army, and less often for reports of losses among Russian military personnel. The investigation and the court usually explain the «deliberate falsity» of these statements by the fact that the Russian Ministry of Defence does not confirm them. During 2022 and 2023, law enforcement officers used this article of the Criminal Code to prosecute opponents of the war more often than others.

- One of the cases initiated under this article that attracted public attention was the case of a resident of the Kaliningrad region, Igor Baryshnikov. In June 2023, he was sentenced to seven and a half years in a general regime colony for publications about the sinking of the cruiser Moskva and the execution of civilians in Ukraine by the Russian military. Baryshnikov had a catheter in his bladder, which was placed due to suspected cancer of the urinary system. It was supposed to be changed monthly, but the employees of the Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN) medical team did this irregularly. Baryshnikov had his prostate adenoma removed, but in order to carry out this operation, it took enormous efforts of lawyers, human rights activists and other concerned people, as well as a special request from the UN Human Rights Committee. Due to the fact that the procedure was constantly postponed, Baryshnikov’s health continued to deteriorate. A circulatory system disorder and a fungus were discovered; in addition, his vision was rapidly deteriorating, and one eye can practically no longer see.

In 2022, 158 people were charged with spreading «fakes». This is more than twice the number of those prosecuted under the article on vandalism (Article 214 of the Criminal Code), which was the second most commonly applied «anti-war» article, following the article on «fake news». In 2023, cases relating to «fakes» were initiated against at least 112 people. Another article specifically crafted to suppress anti-war statements — Article 280.3 of the Criminal Code on «discrediting the Armed Forces» — followed a close second with 101 cases. This law effectively punishes virtually any posts, statements or solitary pickets that could be interpreted as criticism of the war or even calls for peace.

It is worth noting that a criminal case under Part 1 of Article 280.3 of the Criminal Code — the article most frequently used by law enforcement — can only be initiated if the prosecuted person has already been found guilty under a similar administrative article (Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences). Additionally, the next «act of discrediting» must occur within a year of the individual being held administratively liable. This requirement is one of the reasons why the number of criminal cases relating to discrediting the Armed Forces had increased significantly by 2023.

By as early as 2024, though, the number of new criminal cases on discrediting had halved — to 50 cases from 101 in 2023, as the peak in the use of the corresponding administrative article had passed. A similar trend can be observed in the number of people prosecuted in cases of «fakes», the number of which dropped to 61 by 2024 from 112 in 2023.

- In October 2024, in Moscow, the poet and author of the musical project «Dorevolyutsionny Sovetchik» Vyacheslav Malakhov was sentenced to two years in a general regime penal colony under the article on discrediting the Armed Forces. On the day of his arrest, law enforcement officers beat him in a police van as well as threatened to shock him with a stun gun and send him to the war. The reason for his prosecution was a post he made on 8 September 2023, in which he criticised the hypocrisy of the Russian authorities. His post began with the phrase: «No one wants to fuck you in your withered ass, old man, just relax and calm down already.»

The grim first place in the list of the most frequently used criminal articles is currently occupied by the article on calls for terrorist activity or its public justification (Article 205.2 of the Criminal Code). However, we cannot say that the number of people prosecuted under this article for anti-war statements has significantly increased compared to 2023; on the contrary, there were 92 such cases in 2023, while in 2024 the number stood at 87.

- In September 2024, a former deputy from Glazov (a town in the European part of Russia), Andrey Edigarev, was sentenced to three years in a general regime penal colony under this article. In 2022, he took part in the opposition «Congress of People’s Deputies of Russia» in Warsaw before returning to Russia. During his arrest, Edigarev was beaten on the face, stomach and groin and was thrown face-first into the dirt. The case was initiated over his posts, which included phrases such as: «Watching the burning equipment and burning lads, tears come to my eyes. Adolf Putin, you’re dead.» «Well, Putin’s scum, are you ready to go die? Ukrainian bullets are waiting for you, ” and „It’s hard to find a family of stokers or carpenters in Russia, but we sure have a dynasty of FSB officers.“

The decline in the number of cases relating to «fakes» may be due to the fact that most of the crimes attributed to Russian servicemen were committed early in the war. In the following years, statements on that subject became less frequent. However, we are also aware of cases where individuals are prosecuted for statements made one or even two years before the charges were brought against them.

It is also worth mentioning the significant drop in the number of prosecutions under the article on vandalism after 2022. One possible explanation is that some people considered this form of protest too risky and shifted their activities to social media, while others, on the contrary, saw it as too insignificant and turned to more radical actions, such as arson — which we tend to classify as anti-war protests only in rare instances.

The sharp rise in prosecutions under articles on calls for actions against Russia’s security (Article 280.4 of the Criminal Code — another new provision added in July 2022), dissemination of disrespectful information about the days of military glory (Part 4 of Article 354.1 of the Criminal Code) and involvement in the activities of an extremist community (Article 282.1 of the Criminal Code) is largely due to a major case against members of the anti-war movement «Vesna» («Spring») and those whom the investigation deemed affiliated with it. The authorities classified the movement’s activities as extremist (Vesna was officially declared an extremist organisation, but since the actions in the case were committed earlier, the charges fall under the article on participation in an extremist association rather than an extremist organisation). More than 20 people have been charged in this case, six of whom were arrested, while the rest are wanted by the authorities. The prosecution is based on posts published on the movement’s social media pages. The defendants are facing various charges, including under the aforementioned «fake news» article. Charges under Article 280.4 of the Criminal Code were brought for posts calling on Russian servicemen to surrender or refuse to take part in combat. Article 354.1 was applied in response to posts criticising state-approved ways of celebrating Victory Day.

Grounds for Prosecution

Ranking of actions that led to criminal cases

Number of defendants by year when prosecution started and social networks

Over the three years of the war, law enforcement officers have initiated the largest share of «anti-war» criminal cases for statements made online. In 2022, 220 people were prosecuted for publications against the war on social media.

Most of these cases were initiated for posts on VKontakte, which continues to be the most dangerous social media platform in 2024 as well. Telegram comes second, followed by YouTube as the third.

In most instances (85% of those where we were able to identify publication dates), law enforcement officers initiated these cases in 2024 for posts from 2022 and primarily from 2023.

Despite the overall decline in the number of prosecutions initiated in 2024 compared to 2023, the number of prosecutions for online activity remains approximately ten times greater than those related to offline statements (263 vs. 27 in 2023 and 151 vs. 15 in 2024).

In addition to those who spoke out loud in public places, a significant share of the prosecuted individuals, particularly in 2022, are those who wrote anti-war messages on various objects. Their number does not fall far behind the individuals prosecuted for arson (46). Taking into account these figures, as well as the number of people prosecuted for distributing leaflets (28), the total number of individuals prosecuted for statements far exceeds the number of people prosecuted for other types of activity.

In at least a third of the various activities (real or made up by the investigators) that have led to prosecution, there has been a decline in the number of individuals prosecuted since 2023 compared to 2022 (and even more so in 2024), sometimes quite significantly.

- In 2022, arson was the second most «popular» action in «anti-war» cases (with 52 people prosecuted). The number of new «anti-war arsonists» dropped to 20 in 2023 and zero in 2024. One reason for this is that such actions were initially classified under the article on property destruction (Part 2 of Article 167 of the Criminal Code), with relatively mild punishment. However, the same actions were later more often prosecuted under the article on terrorism (Article 205 of the Criminal Code) carrying far harsher penalties, which has likely deterred many people. Additionally, while early on, anti-war activists often carried out actions with relatively low levels of danger (such as throwing flammable liquid at windows of empty buildings causing minimal damage), but over time more people committed or planned to commit (actually or according to the investigation) far riskier actions — such that could have at least disrupted infrastructure unrelated to the war effort, primarily arson of relay boxes on railways. The arsonists or organisers likely intended to block the movement of military convoys. However, as a result of these arson attacks, civilian train services could have been disrupted as well. These instances are often difficult to categorise as purely anti-war activities, and the prosecution of such individuals is less likely to be viewed as politically motivated. It is also worth noting that in 2022, we recorded more instances of prosecution for arson that involved individuals acting alone or in small groups, seemingly driven solely by their own beliefs. Later on, however, individuals prosecuted for arson were more likely to have been involved in negotiations with real or alleged representatives of armed groups fighting on Ukraine’s side and carry out tasks for financial gain. We most often tend to categorise such prosecutions as unrelated to «anti-war» activities. More details on these cases can be found in the relevant sections.

- As for prosecutions on charges of joining armed formations (11 vs. 2 in 2023 and 2024), we identified more instances in 2022 where such charges were not based on anything substantial and were merely an addition to other charges relating to anti-war activities. Later, however, more cases began to emerge — as mentioned above — that were initiated based on message exchanges with representatives of armed formations or with Russian intelligence officers acting in that role. Again, such prosecutions are more difficult to classify as «anti-war».

The only increase in 2023 compared to 2022 was observed in prosecutions relating to membership in a political movement, which is explained by the initiation of the aforementioned case against the Vesna movement.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Defendants

The beginning of the third year of the war was marked by the initiation of a criminal case against the 19-year-old activist Darya Kozyreva for repeatedly discrediting the Russian army (Article 280.3 of the Criminal Code). On the second anniversary of the full-scale invasion, she pasted a poster with a fragment of Taras Shevchenko’s poem «Zaveshanie» («Testament») on the monument to the Ukrainian poet in St. Petersburg.

In total, during 2024, 38 people aged 18 to 30 were charged in «anti-war» criminal cases. Additionally, two charged individuals were minors, including the 15-year-old Kazan resident Sevastyan Sultanov, who was charged with vandalism (Part 2 of Article 214 of the Criminal Code) for graffiti in support of Alexei Navalny.

Despite the high-profile nature of prosecutions against young Russians, such cases remain relatively rare. In 2024, law enforcement agencies initiated fewer «anti-war» cases against individuals aged 18 to 30 than they did in 2022 and 2023. Whereas this age group previously accounted for about a third of all cases, they now make up only 20% of all defendants across all age groups.

The number of new defendants in «anti-war» cases over the age of 50, on the other hand, increased in 2024. At the same time, individuals aged 31 to 50 constitute half of all people prosecuted for their anti-war stance.

Defendants in «anti-war» cases «became older» in 2024

Throughout the three years of the war, journalists have remained the largest group of defendants in «anti-war» criminal cases, with 71 individuals affected. This is not surprising, as these cases are often initiated over posts, comments, statements and other publications, i.e. activities that journalists regularly engage in.

In 2022, the second largest group of defendants in such cases were politicians, who also actively spoke out against the war. However, they were later overtaken by entrepreneurs, against whom criminal cases were initiated more frequently in 2023 and 2024. Nonetheless, the total number of «anti-war» defendants among politicians still exceeds that among entrepreneurs — 66 vs. 62.

Among other large groups of «anti-war» defendants are artists (56 people), bloggers (53 people) and students (46 people), i.e. individuals who, either as part of their primary occupation or as members of active social groups, consistently express their political stance.

10 most common occupations of defendants in «anti-war» cases

Earlier we noted that the proportion of women in «anti-war» cases is higher than in other politically motivated criminal cases (16% women vs. 83,4% men in all politically motivated cases; the gender of 0,6% of individuals is unknown). However, most often, the individuals involved in «anti-war» cases are men. In 2024, this situation did not change: although the share of women among the defendants increased by almost 2% to 20,5%, this cannot be considered a significant majority. The gender of another 0,9% of defendants in cases initiated in 2024 is unknown.

Distribution of defendants in «anti-war» cases by gender

We cannot create a full portrait of the typical defendant in an «anti-war» case: the data on some of the prosecuted individuals are unknown. However, if we take the most common characteristics of individuals in «anti-war» cases, we find that they are typically men between the ages of 31 and 50 who work as journalists.

Convictions

The relatively small number of convictions in «anti-war» cases in 2022 (82 convicted individuals) can be explained by the fact that a significant portion of cases initiated that year only reached a verdict in 2023 (209 people were convicted). When talking about convictions in these cases, it is important to note that they are quite difficult to compare with one another. These cases were initiated under articles of varying severity — ranging from vandalism, which at worst carries a penalty of up to three years in prison, to treason, which can result in life imprisonment. Nevertheless, according to our data, courts most often impose actual imprisonment as punishment. The number of such sentences was especially large in 2023 and 2024 when many «anti-war» cases reached the stage of announcing the verdict. Fines come second by a large margin, and all other forms of punishment lag further behind in terms of their frequency.

Individuals charged in «anti-war» cases are most often sentenced to relatively long terms of imprisonment, ranging from four to almost seven years and from seven to almost ten years (the number of such sentences in 2024 grew by more than a third compared to 2023), with sentences of two to almost three years coming third.

When analysing punishments imposed in cases initiated for the most «popular» articles (we can only compare cases where only one article was applied), the picture is unique in each case. Cases initiated under the article on «fakes» most often result in actual imprisonment, while 2024 saw a significant number of sentences passed in absentia.

Interestingly, most of the punishments in cases related to calls for terrorism or public justification of terrorism in 2023 were fines; in 2024, imprisonment became more prevalent, and the overall number of convictions for this article in 2024 was significantly higher than in 2023. This may be explained by the fact that a substantial portion of these cases were initiated in 2023 and reached verdicts in 2024.

A fine remained the most «popular» punishment in cases of discrediting the Armed Forces in 2023 and 2024. The number of prison sentences under this article in 2024 increased compared to the previous year, albeit not significantly (from 10 to 17), despite the fact that punishment for this article was tightened in December 2023. This is likely due to the fact that most cases still continue to be initiated for posts published before December 2023.

Share of actual prison sentences among other convictions in anti-war criminal cases

The average length of prison sentences for defendants in «anti-war» cases is increasing

Distribution of sentences by categories of prison terms

Types of sentences for the most commonly applied articles

Other Criminal Cases Related to the War

As we have already mentioned above, we observe and work not only on politically motivated criminal cases based on anti-war protests or statements, but also on ones related to the war in a wider sense (sometimes this relation may be even only an assumption). There is a large variety in the types of «anti-war» cases: messages on social media and setting fire to a military recruitment office have little in common. However, what all these cases do have in common is the anti-war motive in the actions of the prosecuted individual. The prosecutions that are the topic of this section often share no characteristics apart from their general relation to the war, which in some cases we only assume to be there.

Среди них можно выделить:

The following are among them:

- «anti-war» cases; these could be charges of arson, potentially more dangerous compared to setting fire to windows of military recruitment offices in the middle of the night as a symbol of supporting the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) or encouraging calls for such actions (an example of this is the case of Ibragim Orudzhev, a student who was sentenced to 16 years in a strict regime colony: the prosecution believes he had planned to set fire not only to a military recruitment office, but also to the buildings of other government agencies);

- Prosecutions of Ukrainian soldiers and other people associated with the AFU, captured, but charged under Russian legislation as civilians, mainly under terrorist charges (including the cases of people charged with serving in the Azov Brigade and people charged with serving in the Aidar Batallion);

- Prosecutions of residents of the occupied and annexed territories on charges of terrorism (for example, the case of Irina Navalnaya, a resident of Mariupol, who supposedly planned an explosion on the day when the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) was holding a referendum on joining the Russian Federation as one of its new territories);

- Prosecutions for statements made by Ukrainian citizens, including public figures (for instance, Dnipro’s mayor Boris Filatov) as well as regular residents of the occupied and annexed territories;

- Prosecutions of people to whose actions the investigators attribute an anti-war motive, which may not have even been there, or people charged with making statements that do not belong to them (this group of examples includes the case of Ural’s anti-fascists, i.e. the «Tyumen’s case» where six young people are charged with involvement in a terrorist organisation whose plans included sabotage on the railways that Russian trains use to carry military vehicles and equipment to Ukraine);

- Prosecutions of people whose actions were related to the war (for example, people who helped Ukrainian refugees, such as the instance of Alexander Demidenko, a resident of the Belgorod region charged with illicit trafficking of explosive devices who died in custody), but it is unknown whether the prosecution itself is related to the war;

- Prosecutions, the grounds for which could be anti-war statements or performances, but we cannot confirm it with certainty (for example, the businessman and philanthropist Boris Zimin, who has repeatedly spoken out against the war, is charged with fraud; he himself considers the case politically motivated, but we have no more compelling arguments);

- Prosecutions where the war is mentioned as an aggravating circumstance (for example, four residents of the Rostov region facing prosecution for their involvement in the Islamic extremist movement Tablighi Jamaat — a movement officially recognised as an extremist organisation without any legal justification — are charged with, in particular, «denying the necessity for Russian Muslims to participate in the special military operation»);

- Prosecutions for actions related to the war which, however, cannot be called anti-war (for example, prosecutions of journalists covering the war);

- Prosecutions of people who have become victims of scammers (if the cases mention the war, as, for example, in the case of Vera Nikolaeva and Anastasia Lysenkova, who wrote «GUR» (which stands for Ukraine’s «Main Directorate of Intelligence») on the monument to Zhukov);

- Prosecutions of supporters of the war who have fallen out of political favour (such as, first of all, the former «minister of defence» of the self-proclaimed DPR Igor Strelkov, sentenced to four years on charges of calls for extremism)

Similarly to «anti-war» prosecutions, the region with the highest number of them is Moscow (51 people). The Rostov region comes second with 38 prosecuted people and the third place is occupied by Crimea (21 people). In Moscow, the number of prosecuted individuals in 2023 increased compared to 2022 (to 19 up from 15), but dropped slightly in 2024 (to 11). In the annexed Crimea, we see a sharp drop already in 2023 (from 16 down to 3). The drop is even greater in the Rostov region (from 33 down to 1), where many Ukrainian prisoners of war charged with terrorist crimes are being tried. We attribute these prosecutions to the Rostov region, even though these people were taken prisoner in the occupied territory of Ukraine, because what happens on the occupied territories in the time of war is less known to us and often goes beyond the scope of criminal proceedings.

As for prosecutions under criminal articles, all leading positions are occupied by articles related to terrorism, as well as the article on forcible seizure of power (Article 278 of the Criminal Code). The highest number of people (56) were prosecuted under the article on involvement in the activities of a terrorist organisation (Article 205.5 of the Criminal Code). This article was used to bring charges against Ukrainian prisoners of war for their alleged relations to the Azov and Aidar battalions, which were recognised as terrorist organisations in the Russian Federation, while in recent years these formations have in fact become regular units of the Ukrainian army. Approximately the same number of people (54) were prosecuted under the article on public justification of terrorism or calls for terrorism (Article 205.2 of the Criminal Code). The article on forcible seizure of power comes third (42 people) and was also used to prosecute Ukrainian prisoners of war who are charged with seizing power in the self-proclaimed DPR, while at the time the incriminated actions were committed the DPR was not recognised even by the Russian Federation as a country. Then there are articles on receiving training for terrorist activities (Article 205.3 of the Criminal Code, 30 people), committing terrorist acts (Article 205 of the Criminal Code, 23 people) and involvement in the activities of a terrorist community (Article 205.4 of the Criminal Code, 22 people).

Mass cases against Ukrainian military personnel were initiated in 2022, which explains the significant decrease in the number of individuals prosecuted for involvement in a terrorist organisation (from 43 down to 8 in 2023 and 3 in 2024), seizure of power (42 in 2022, zero in the following years), training for terrorist activities (23 in 2022, 4 in 2023 and 1 in 2024), and involvement in the activities of a terrorist community (17, 1 and 2 people, respectively). In contrast, the number of people prosecuted for calls to terrorism increased significantly in 2023 compared to 2022 (from 7 to 20) and the number of new prosecutions in 2024 remained at the same level (19).

The number of individuals prosecuted for online statements is also high (49 people). But even taken together with other people prosecuted for statements (12 for «offline» statements, 7 for leaflets and 6 for inscriptions), it does not exceed the number of people prosecuted for joining the AFU (71 people) — this number includes cases initiated against Ukrainian prisoners of war. But while the number of people prosecuted for military service dropped sharply already in 2023 (from 57 down to 11 and further to 3 in 2024), the number of individuals prosecuted for online statements, on the contrary, increased (from 8 to 17 in 2023 and 22 in 2024). Arson makes up a relatively small portion of these cases (15 people). As we have noted above, we have no basis or have insufficient data to count many cases of arson as politically motivated.

Deprivation of liberty is the most often imposed type of punishment, and the number of people subjected to such punishment increases each year. The number of sentences to all other types of punishment is significantly lower: at least 111 people were sentenced to imprisonment, not counting those sentenced in absentia, and seven people were sentenced to fine payments. In terms of the duration of imprisonment, sentences of four to almost seven years are imposed most often (there was a significant increase in the number of sentences by 2024), followed by sentences of seven to almost ten years and ten to almost 15 years (the second group also shows a significant jump in the number of sentences handed down in 2024).

In the process of observing war-related prosecutions, we identified the need to record all charges of particularly serious crimes, as well as cases brought against servicemen for refusing to serve. This is how our project «Prisoners of the Wartime» has come into being. At this stage, the project’s focus also includes some of the people prosecuted in «anti-war» cases, as well as people referred to in the section «Other Criminal Cases Related to the War», and even those whose cases we do not consider politically motivated.

Prisoners of the Wartime

Reasons for opening cases of arson and providing assistance to the Ukrainian army in 2024

The breakout of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has led to an increase in the number of prosecutions for treason, terrorism and sabotage. This is a result of both a more radical way of expressing protest against the actions of the Russian authorities, as well as the government’s desire to create a picture of an intense struggle against «internal enemies». The defendants in such cases face unjustifiably long prison sentences, fabricated evidence, provocation and torture, which makes it crucial to monitor such cases. While we do not always know whether the defendants have in fact committed what they are charged with or what their position is, and in many cases we are not sure whether their prosecution can be considered politically motivated, we believe it is important to provide the fullest possible picture of repression going on in the country.

Criminal cases of setting fire to military recruitment offices, local administration buildings, railways and other facilities

Arson of military recruitment offices, especially in the first year of the war, was not so much a way of inflicting real damage to the war machine, as it was an expression of desperation stemming from the Russian invasion of Ukraine. According to Mediazona, in the first months of the war — from February to November 2022 — there were 75 arson attacks on military recruitment offices, administrative buildings and other facilities in Russia motivated by anti-war protest. Furthermore, 34 of those arsons were committed between 24 February and 21 September — before the announcement of the partial mobilisation — while after 21 September, 41 arsons were committed during a little more than a month.

- One of the first known cases is the case against the Moscow resident Kirill Butylin, who was sentenced to 13 years of imprisonment for committing a terrorist act (Article 205 of the Criminal Code), public calls for terrorism (Part 2 of Article 205.2 of the Criminal Code) and vandalism motivated by political hatred (Part 2 of Article 214 of the Criminal Code) in March 2023. According to the investigation, on 28 February 2022 Butylin threw several Molotov cocktails at the military recruitment office in the Moscow region. On 8 March, the telegram channel «Vata-Hunters» («ВатаХантеры» in Russian) published a video of the attack and the arsonist’s manifesto, in which he spoke against Russia’s war in Ukraine. On the same day, the man was detained at the border of Lithuania and Belarus — when he was about to leave for Ukraine to fight on their side, according to law enforcement.

The year 2023 saw far fewer arson attacks on military recruitment offices and administrative buildings motivated by anti-war sentiment, and a significant share of the attacks were committed by victims of fraud. A massive wave of arson attacks occurred in late July and early August 2023: at least 37 fraudster-induced attacks were committed during that period, as counted by Mediazona. In 2024, fraudsters organised at least 92 attacks on various objects, 65 of which occurred between 13 and 27 December.

As a rule, people who set fire to military recruitment offices with anti-war motives are charged with committing a terrorist act. In some cases, other serious articles and new charges are added to the charge, such as participation in the Azov Battalion or attempting to join the Ukrainian army, which allows courts to impose long prison sentences.

- In May 2024, Novosibirsk resident Ilya Baburin was sentenced to 25 years of imprisonment with the first five years to be served in prison for a failed arson attack on a military recruitment office. He was initially charged only with an attempt to organise a terrorist act (Part 1 of Article 205 of the Criminal Code with the application of Part 3 of Article 30 and Part 3 of Article 33 of the Criminal Code). Later, Baburin was also charged with treason (Article 275 of the Criminal Code), illegal trafficking of technical means for covert acquisition of information (Article 138.1 of the Criminal Code), participation in an illegal armed formation (Part 2 of Article 208 of the Criminal Code), participation in the activities of a terrorist organisation (Part 2 of Article 205.5 of the Criminal Code) and committing a terrorist act (Part 1 of Article 205 of the Criminal Code).

As a rule, victims of fraud are charged with intentionally damaging property (Article 167 of the Criminal Code). In some cases, the defendants in such cases are charged with committing or attempting to commit a terrorist act, despite the fact that they did so unintentionally.

- In January 2025, Galina Ivanova, a 76-year-old woman from St. Petersburg, was sentenced to ten years in a penal colony in the case of arson of a car parked near a military recruitment office. The woman was found guilty in the case of a terrorist act causing significant property damage (Point «c» of Part 2 of Article 205 of the Criminal Code).

Another category of arson cases involves damage to railway infrastructure. Initially, the arsonists assumed that this would slow down the movement of trains that deliver arms to the Russian military. However, either no real damage was done to military supplies, or damage was also done to civilian transportation.

From the beginning of the war to October 2023, at least 137 people were charged in such cases, and at least 76 such cases were initiated overall, as estimated by Mediazona.

By 2024, the majority of such arsons, as follows from official materials, had begun to be committed in exchange for money. Such arsonists are no longer targeting just railways, but also energy facilities, electricity pylons and other sites. According to approximate data from OVD-Info, in 2024 and in the first two months of 2025, 202 people were charged in cases of arson and explosions, with at least 62 of them minors.

In addition, several new criminal articles were introduced into the Criminal Code at the end of 2022:

- Article 281.1 — Facilitating sabotage activity;

- Article 281.2 — Receiving training for sabotage activity;

- Article 281.3 — Establishing a sabotage community and participation in it.

In 2024, law enforcement officers began to initiate criminal cases under these articles. For instance, they appeared in the case of the Ukrainian citizen Sergey Karmazin, who, according to law enforcement, set fire to two relay boxes in the Moscow region. Initially he was charged only with the article on committing sabotage (Part 2 «a» of Article 281 of the Criminal Code). However, within a year he was also charged under the articles on espionage (Article 276 of the Criminal Code), receiving training in sabotage activities (Article 281.2 of the Criminal Code), preparation for the manufacture of explosives (Part 3 of Article 223.1 of the Criminal Code with the application of Part 1 of Article 30 of the Criminal Code), participation in a sabotage community (Part 2 of Article 281.3 of the Criminal Code), participation in a terrorist community (Part 2 of Article 205.4 of the Criminal Code), preparation for a terrorist act (Part 1 «a» of Part 2 of Article 205 of the Criminal Code with the application of Part 1 of Article 30 of the Criminal Code) and terrorist training (Article 205.3 of the Criminal Code). In March, Karmazin was sentenced to 25 years of imprisonment with the first six years to be served in prison.

In some cases, as reported by the defendants themselves and their lawyers, criminal cases may be initiated following provocations by Russian intelligence services. As a rule, law enforcement officers contact activists and opponents of the war, present themselves as members of the Ukrainian intelligence services or soldiers of the AFU and ask them to commit arson of an infrastructure or administrative facility in exchange for financial reward or other incentives, such as residence permits in European countries. The provocations are indirectly confirmed by the fact that some of the defendants are detained on their way to the place of the alleged crime. It is impossible to count the number of such criminal cases that have been initiated, but we are aware of dozens of such cases.

- In June 2023, Valeria Zotova, a resident of Yaroslavl, was sentenced to six years in a general regime penal colony for attempting to commit a terrorist act (Part 1 of Article 205 of the Criminal Code with the application of Part 3 of Article 30 of the Criminal Code). According to law enforcement, the woman tried to set fire to a humanitarian aid collection point for Donbas «on the orders of the AFU». In July, her defence said that she had been provoked to commit the attempted arson by FSB officers, who exchanged messages with her on behalf of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) officers. One of the main witnesses for the prosecution was her friend Karina, who had persuaded Zotova to agree to the law enforcement officers’ proposal. In court, she said that she participated in an operational-investigative activity, which she called an «operational experiment».

Cases of Treason and Espionage

In July 2022, the Criminal Code was expanded with a new article on confidential cooperation with a foreign state or organisation (Article 275.1 of the Criminal Code), and the maximum penalty for treason (Article 275 of the Criminal Code) increased to life imprisonment. The article also introduced a new form of treason — «switching to the enemy side». A new wording was also added to the article on espionage (Article 276 of the Criminal Code): now it also includes a transfer, collection, theft or storage of information in conditions of armed conflict or military operations «with the aim of transferring it to the enemy».

In December 2024, the State Duma adopted in the second reading amendments that, according to human rights activists, will allow the authorities to initiate more criminal cases of treason and espionage. The document specifies the concept of an «enemy»: international and foreign organisations that «directly oppose the Russian Federation» in an armed conflict. Switching to the enemy side should also include «voluntary participation in the activities of government agencies, institutions, enterprises and organisations of the enemy, knowingly directed against the security of the Russian Federation». These amendments also propose to introduce a new article into the Criminal Code — Article 276.1 on assisting the enemy in its activities against Russia. Punishments under this article will range from 10 to 15 years.

According to the data of Department One («Pervy otdel» in Russian), since the beginning of the Russian invasion, cases of treason (Article 275 of the Criminal Code), confidential cooperation with a foreign state (Article 275.1 of the Criminal Code) and espionage (Article 276 of the Criminal Code) have been initiated against 792 people. Since February 2022, 536 people have been convicted in such cases, with 359 people convicted in 2024 alone. According to OVD-Info data, at least 30 of them are residents of the occupied territories of Ukraine. Most of these criminal cases are likely related to the Russian invasion.

Articles on treason and confidential cooperation with a foreign state have been applied against anti-war activists and those who helped the Ukrainian army. Residents of the occupied territories of Ukraine who did not obtain Russian passports are being charged with espionage: according to the investigation, they passed information about Russian soldiers to the Ukrainian army.

- In August, the Kherson resident Iryna Horobtsova was sentenced to ten years and six months in a general regime penal colony for espionage (Article 276 of the Criminal Code). During the occupation, she helped local residents with food and medicine, wrote posts in support of the Ukrainian military and hung a Ukrainian flag at home. In May 2022, Gorobtsova was kidnapped by Russian law enforcement officers. Information about the criminal case of espionage against her emerged only in March 2024. According to law enforcement, she passed data on the movements of the Russian army in the Kherson region to Ukrainian servicemen.

Defendants may be charged with both treason and participation in the activities of a terrorist organisation (Part 2 of Article 205.5 of the Criminal Code) for attempts to join the Freedom of Russia Legion or the Russian Volunteer Corps (RVC). In some cases, they may be charged under both articles at once. They may face prosecution for actions other than preparing to participate in military action. For example, the Nemtsov Bridge volunteer Yevgeny Mishchenko is facing charges for his messages exchanged with the legion, in which he offered his dacha (summer cottage) plot for the placement of rocket launchers and expressed his willingness to monitor Russian military facilities. He then allegedly filmed a military airfield in Kubinka and sent the materials to the legion. In October, Mishchenko was sentenced to 12 years of imprisonment with the first three years to be served in prison.

In such criminal cases, Russian courts impose long prison sentences. More «lenient» sentences are imposed under the article on confidential cooperation with a foreign state or in instances where the offence is considered incomplete.

Cases against Ukrainian Military and Civilian Prisoners of War

Criminal cases against prisoners of war are initiated not only on possibly trumped-up charges of war crimes, but also because of the very fact of their military service.

The largest such case was initiated against 9 women and 17 men, who are charged with serving in the Ukrainian Azov battalion. They are charged with violent seizure of power (Article 278 of the Criminal Code) and organising the activities of, or participating in, a terrorist organisation (Parts 1 and 2 of Article 205.5 of the Criminal Code). Another 11 men are charged with training to carry out terrorist activities (Article 205.3 of the Criminal Code). Another defendant, Alexander Ishchenko, died in Russian pre-trial detention in July 2024 due to rib fractures, blunt chest trauma and shock. In August, the prosecution requested sentences ranging from 16 to 24 years for the defendants. In September, the women and two men were returned to Ukraine as part of a prisoner exchange.

In 2024, law enforcement officers began initiating criminal cases against Ukrainian soldiers who surrendered during the offensive in the Kursk region. In December 2024, the 2nd Western District Military Court in Moscow sentenced Ukrainian servicemen Vitaliy Panchenko and Ivan Dmytrakov to 15 and 14 years in prison, respectively. The men were charged with committing a terrorist act by prior agreement (Parts 2(a) and 2© of Article 205 of the Criminal Code). According to the investigation, Panchenko and Dmytrakov, who served in the 61st Separate Mechanised Brigade of the AFU, illegally crossed the Russian border on 7 August and «repeatedly opened fire to kill Russian servicemen as well as civilians».

Civilians are also held captive in Russia and the occupied territories of Ukraine — they are peaceful citizens detained by the Russian authorities without any charges brought against them. According to estimates by the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights (Ombudsman) Dmytro Lubinets, Russia may be holding up to 28,000 Ukrainian civilian hostages, though verified information is available only on around 1,700 people. Some civilians are later charged with espionage, treason or preparing acts of sabotage and terrorism against Russian soldiers and the occupying authorities.

Cases Relating to Refusal to Serve in the Russian Army

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, 16,120 cases related to refusal to serve in the Russian army have been filed in courts. Such servicemen have criminal cases initiated against them for failure to comply with orders (Article 332 of the Criminal Code), unauthorised abandonment of a military unit (Article 337 of the Criminal Code) and desertion (Article 338 of the Criminal Code). According to Mediazona, 1,037 cases have been initiated for failure to comply with orders (Article 332 of the Criminal Code) and 683 cases for desertion (Article 338 of the Criminal Code). In 2024, Russian courts received a record 10,308 criminal cases against people who refused to serve in the Russian army. This is almost twice as many as in 2023, when courts registered 5,517 such cases.

In most cases, the reasons why soldiers refuse to participate in military actions are unknown. Some explain their decision by incompetent leadership, reluctance to engage in combat or other reasons. Little is known about objectors on the grounds of religion or ideology.

- In 2023, the believers Maksim Makushin, Vyacheslav Reznychenko and Andrey Kapatsyna were sentenced to various terms. They were all convicted for failure to comply with an order of their commander during a military operation (Part 2.1 of Article 332 of the Criminal Code). The men refused to participate in military actions.

- In October 2024, former senior lieutenant Dmitry Vasilets who refused, for religious reasons, to return to the front line following his vacation, was released on parole. In April, he was sentenced to two years and five months in a settlement colony under the article on failure to comply with an order of the commander given in the context of armed conflict or military operations (Part 2.1 of Article 332 of the Criminal Code). Later, his sentence was reduced by three months on appeal.

Mediazona found that 40% of individuals convicted in such cases receive suspended sentences, which allows the authorities to return them to military service. At the same time, individuals convicted to actual prison terms are sometimes also sent back to the combat zone. In such cases, they are recruited to fight directly from places of detention.

Torture of Defendants and Deaths in Detention

Defendants in such cases often report torture by law enforcement. Typically, law enforcement officers resort to such practices in order to obtain confessions. Some defendants already retract their statements at the stage of judicial investigation, saying they had testified against themselves under duress. According to OVD-Info data, at least 34 instances of detainees reporting torture have been documented.

At least seven people have died during detention or investigation. One of them, the anarchist Roman Shvedov, committed suicide on 18 December, just hours after being sentenced to 16 years in a colony for setting fire to a government building in the Rostov region. Another seven people died during detention: six of them, according to law enforcement, allegedly resisted FSB officers, and one died from a self-detonating explosive device.

Administrative Prosecution

Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences (Discrediting the Armed Forces)

cases under Article 20.3.3 (discrediting the armed forces) were filed in first-instance courts from 24 February 2022 to 17 February 2025

Last year, the trend of a gradual decrease in the number of cases filed in courts continued; however, it is important to note that more than two thousand cases in the third year of the war and anti-war repression is not a small number. It should also be noted that, with high probability, many of the cases in 2024 are initiated not only for new posts but also for ones published back in 2022. We analysed 549 cases filed in first-instance courts from January to September 2024. In 175 of these, we were able to determine the date of the post — 67% of the publications were made before 2024, with 34% made as early as 2022. Extrapolating this number to all cases initiated under Article 20.3.3, we can assume that the number of cases relating to discrediting the Russian Armed Forces depends not only on the presence of new posts or the levels of anti-war sentiments, but also on how easily both the post and its author can be identified, on the work of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in the region and on other factors.

Decisions

Number of administrative cases on discrediting the army filed in first-instance courts

The highest number of cases of discreditation over the years was filed in the courts of the annexed territory of Crimea and Sevastopol. Only in 2022 did other regions of Russia (Moscow and St. Petersburg) see more cases filed in courts; in 2023 and 2024, Crimea took the lead. This may indicate both a high level of resistance to the war in the region and the high activity of local law enforcement agencies and pro-government activists who assist them — in particular, the author of the Telegram channel «Crimean SMERSH» Alexander Talipov.

Article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences (Propaganda or public display of Nazi attributes or attributes of extremist organisations)

Since the start of the full-scale invasion, Russian authorities have considered various symbols associated with Ukraine to be extremist — in particular, the attributes of the Azov Regiment, the slogan «Glory to Ukraine» and a depiction of the trident.

Last year, the number of cases filed in first-instance courts in relation to these symbols was twice as high as in 2023 (when 150 cases were filed compared to 321 in 2024).

Article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences imposes smaller fines than the article on discrediting the Russian Armed Forces. However, it allows for administrative arrest as a punishment, which is frequently practiced. For example, a court in Moscow sentenced Sergei M. to 5 days of administrative arrest for having a Ukrainian coat of arms on his Russian passport cover, a court in Sevastopol sentenced Evgeny Lebidko to 15 days of arrest for shouting «Slava Ukraine» (Glory to Ukraine) and playing the song «Chervona Kalyna» and a court in Karelia sentenced a local resident, S. Senokosov, to 10 days of arrest for a trident tattoo.

Article 20.3.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences — «Public calls for actions aimed at violating the territorial integrity»

From 24 February 2022 to 17 February 2025, 125 cases under Article 20.3.2 («Calls for violating territorial integrity») were filed in courts of first instance.

cases under Article 20.3.2 («Calls for violating territorial integrity») were filed in courts of first instance.

From 24 February 2022 to 17 February 2025

In such cases, fines can be imposed, for instance, for a YouTube video titled «Statement of renunciation of Russian citizenship», a photo of a Ukrainian passport with the caption «Crimea is Ukraine», comments in a Telegram chat about the occupation of Crimea and the independence of Tatarstan, or a comment on VKontakte «that contains a positive view of Smolensk’s secession from Russia and its incorporation into Belarus».

Extrajudicial Pressure

Types of extrajudicial pressure applied against individuals holding anti-war positions from 2022 to 2025

The types of extrajudicial pressure widely used against government opponents before the full-scale invasion remain largely unchanged, although their number — or the number of reports about their use, since we can only count publicly known instances — has significantly decreased over the past year. This decline in persecution is unsurprising and may be attributed to the war going on for three years already, so people understand the consequences of anti-war statements, as well as to the decrease in the number of such news published, likely due to the pressure on regional independent media outlets, human rights defenders and activists.

However, there is one region where the number of such persecutions, if decreasing at all, is doing so only slightly. It is Crimea, with the thriving Telegram channel Crimean SMERSH run by the pro-government activist Alexander Talipov, who actively fights against opponents of the war and helps law enforcement persecute them. This channel publishes videos of Crimeans apologising for things such as a speaker placed in a window playing Ukrainian songs, a playlist of Ukrainian songs on VKontakte, a Russian flag erased from their licence plates or a passport cover with a Ukrainian flag on it (the cover shown on the video was forced to be burned). People were even forced to apologise for «mocking the activities of the Crimean SMERSH». Talipov is also actively working with denunciations made by local residents: for example, apologies were demanded from Nelly Karamyan, who called Crimeans occupants at a bus stop, and from Yuri Fandyushkin for «speaking out against the special military operation, discrediting the army and the country» in a private conversation among colleagues and «ordinary citizens».

All people whose apologies are subsequently shown on Crimean SMERSH are prosecuted in administrative and sometimes criminal cases. In addition to judicial prosecution, there are other consequences. For example, the lawyer Alexei Ladin was prosecuted for discrediting the army and demonstration of Nazi symbols after publications that appeared in the Crimean SMERSH, and was later stripped of his attorney’s licence. Similarly, the teacher Medina Bekirova was first forced to apologise for posts containing Ukrainian symbols and was later fired.

Among people most frequently subjected to extrajudicial persecution in the past year were teachers and professors, as well as clergy who expressed anti-war views. For example, at least nine teachers were fired last year for their anti-war stance or statements.

The clergy faced the following consequences for expressing anti-war views:

- In Chelyabinsk, the priest Petr Ustinov was prohibited from serving for his refusal to read the «Prayer for Holy Russia», which asks for victory;

- In Moscow, the Russian Orthodox Church banned the priest Konstantin Kokora from performing his duties for refusing to recite the same prayer. Furthermore, the Moscow Diocesan Court stripped the priest Andrei Kudrin of his priesthood after he had spent two years reciting a prayer for the reconciliation of the Russian and Ukrainian peoples in lieu of the official «Prayer for Holy Russia»;

- In Novosibirsk, the priest Vadim Perminov was dismissed from the Russian Orthodox Church for refusing to read a prayer for Russia’s victory in the war with Ukraine.

In the past year, another practice of refusing to issue or revoking internal ID documents and passports of anti-war activists became widespread as well. Among those affected were Richard King and Daniil Chebykin, the founders of the «Omsk Civil Association» who currently live abroad, as well as the anti-war activist Olesya Krivtsova. In addition, cases of revocation of citizenship for statements against the war or support for Ukraine were documented, including that of Vladislav Cherkashin, who is in Armenia, and a 57-year-old woman born in the city of Lysychansk, located in the so-called LPR under Russian occupation.

Legislation

The government has been consistently tightening the laws on military censorship, as well as on mobilization, international cooperation and historical remembrance since the start of the full-scale invasion.

Last year, at least eight repressive laws were adopted — a large part was aimed at the fight against foreign agents. This section is dedicated to the laws concerning actions against the war in Ukraine — the rest are described in our Repression in 2024 report.

For instance, in February 2024 the government passed a law providing for confiscation of property gained as a result of committing «crimes» under the articles on spreading «fakes» about the Russian army (Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code) and public calls to activities against the safety of the state (Article 280.4 of the Criminal Code) — in both cases «with selfish intent». Moreover, the law expanded the range of articles under which the convicted individual can be stripped of awards, ranks and titles: it now includes the article on «fakes» (Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code), discreditation of the Russian Armed Forces (Article 280.3 of the Criminal Code), rehabilitation of Nazism (Article 354.1 of the Criminal Code), incitement of hatred and enmity (Part 1 of Article 282 of the Criminal Code) and other articles often invoked in politically motivated cases.

On 28 December 2024, a law amending the federal laws «On prevention and counteraction to legalisation (laundering) of proceeds of crime or terrorist financing» and «On prevention of extremist actions» came into effect. The government has expanded the criteria for adding citizens and organisations to the Rosfinmonitoring (Russia’s financial transaction control agency) blacklist, which contains information on persons connected to terrorism and extremism. The new version of the law allows for the inclusion of individuals suspected of any crime motivated by hatred or enmity — including people convicted of spreading «faces» about the Russian army out of hatred (Part 2(d) of Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code) as well as under the articles on genocide (Article 357 of the Criminal Code) and violation of the territorial integrity of the country (Article 280.2 of the Criminal Code).

On that same day, a law broadening the definition of «switching to the enemy side» in the article on treason (Article 275 of the Criminal Code) and toughening the punishment for armed mutiny (Article 279 of the Criminal Code) came into effect as well. There are no doubts that these new versions of the articles on treason will also be used in cases related to the ongoing war — the practice of using these articles in cases relating to collaboration with the Freedom of Russia Legion is already in place.

In December 2024 the parliament also passed in the first reading a bill that criminalises performing illegal investigative actions in Russia based on foreign criminal cases. One of the authors of the bill, Vasily Piskarev, clarified that the article will be used to punish, in particular, «international cross-border contacts that bypass our laws and international treaties with goals that counteract the interests of our country» or «motivation of Russian citizens to testify in criminal cases investigated abroad». Most of such criminal cases are related to war crimes committed by Russian soldiers and the Russian state in the territory of Ukraine.

As recently as this year, State Duma members proposed a bill that expands the responsibility for failing to report crimes. Aside from failing to report past or planned crimes classified as terrorism, the authors propose to also punish a failure to report crimes under four Criminal Code articles on «sabotage», three of which have been introduced since the start of the full-scale invasion. In a clarification note, the lawmakers explained that «during the special military operation the Russian Federation has experienced an increase in the number of acts of sabotage against important installations» while «some citizens remain silent about attempts to coerce them to committing illegal actions, which negatively affects the ability of law enforcement agencies to obtain relevant information» on planned acts of sabotage «in a timely manner».

«Foreign Agents» and «Undesirable Organisations»

Since the start of the full-scale war, people are often added to the lists of «foreign agents» with justifications such as «[he] spoke up against the special military operation in Ukraine», «spread… false information aimed at forming a negative image of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation» or «openly supported Ukraine». The list of «undesirable organisations» is expanded with organisations involved in supporting Ukraine, anti-war initiatives as well as think-tanks and political organisations that study the war, repression and opposition to them.

The overwhelming majority of additions to the lists of «foreign agents» and «undesirable organisations» due to the war in Ukraine constitute media outlets and journalists. Various political groups are more often considered «foreign agents» than «undesirable organisations», but human rights groups are classified as «foreign agents» about as often as «undesirable organisations» (18 vs. 14). Musicians, artists, performers and art organisations are more often added to the list of «foreign agents», while think-tanks come fourth among both «foreign agents» and «undesirable organisations».

38 anti-war «foreign agent» and «undesirable» organisations were involved in supporting local or ethnic groups and indigenous people: this is one of the ways the government fights decolonisation, which became a popular topic since the start of the full-scale invasion, as well as grassroots organisations which it considers dangerous.

An analysis of the occupations of the people and activities of the organisations that have gained these toxic labels reveals that they occupy the parts of society that the government wants to either control entirely or make outright illegal.

At least 74 «foreign agents» are facing charges in «anti-war cases». 54 of them are prosecuted for «fakes» about the Russian army, 15 for public justification of terrorism and another 7 for discrediting the Russian army. Moreover, most of them (41) were charged under anti-war criminal articles first and were added to the «foreign agent» list only at a later stage.

Blocking, Censorship and Pressure on Journalists

Since the start of the full-scale invasion, the Russian government has monitored the spreading of information about the situation on the frontline. That includes limiting access to information by blocking it through ISPs. In March 2022, Instagram and Facebook were blocked because these social networks, according to Roskomnadzor (Russia’s internet watchdog agency) were «being used to spread informational materials containing calls to violence against Russian citizens and military personnel». Russian users started installing VPNs to get access to blocked media, websites and banned social networks.

websites were affected by wartime censorship According to the data of Roskomsvoboda, from 24 February 2022 to 13 February 2025

Roskomsvoboda defines wartime censorship as blocking of websites that, according to the Russian government, spread «materials discrediting the Russian armed forces» or «fakes about the military».

According to a Roskomsvoboda report, the Russian government is planning to increase the budget for technical means of counteracting threats in order to block VPN services in Russia. Alongside that, a law that forbids spreading information on ways of bypassing Internet censorship with the help of VPNs was passed in 2024.

journalists and bloggers are imprisoned for politically motivated anti-war criminal cases right now

According to OVD-Info data as of 20 February 2025

Journalists charged in politically motivated anti-war criminal cases

In total, 144 journalists, bloggers and media workers have been charged in politically motivated anti-war criminal cases since the start of the full-scale invasion. That includes 15 foreign journalists against whom the FSB has initiated a case for their work in the Kursk region.

Resistance to Repression and Solidarity

The three years of full-scale war against Ukraine that has taken thousands of lives and changed the lives of many readers of this report, mass repression in Russia, hundreds of new victims of political persecution, murders of political prisoners, media bans, the prosecution of journalists, teachers, lawyers and human rights advocates, pressure of propaganda and the possibly fundamental disagreements with loved ones — all of this can seriously confuse the reader, evoke absolute despair and dread. We understand these feelings. Having said that and not trying to belittle these terrible events, we still consider it important to draw the attention of the reader to some positive developments — stories of successful resistance to repression, prosecuted people being released, having the conditions of their detention improved and so on. All of this is possible even in these difficult times. We consider it important to highlight the incredible effort of the people who move mountains to make these improvements happen no matter what.

First, we would like to focus on positive developments in cases concerning people suffering from the military aggression — the residents of Ukraine. By various accounts, thousands of Ukrainian civilians were kidnapped, many of them are being held in terrible conditions without any legal status and with no way of contacting the outside world. The woes of war afflict not only adults, but children as well — it is enough to recall the multiple instances of relocating Ukrainian children to Russia. Helping them in these instances requires huge effort. However, in the last three years, some civilian hostages and relocated minors have returned home or had a chance to meet their loved ones.

August 2024 saw one of the most important events in the modern history of political prosecution — a prisoner exchange between Russia and Belarus on one side and the USA, Germany, Poland, Slovenia and Norway on the other. 15 prisoners from Russia and one from Belarus were freed and deported to Germany and the USA. 13 of the people released from Russian detention centres and penal colonies had faced political prosecution.

Five of them were prosecuted for their anti-war statements:

- The opposition politician Vladimir Kara-Murza was sentenced to 25 years in a strict regime colony on charges of spreading «fakes» about the Armed Forces, treason, and involvement in the activities of an «undesirable organisation» (the latter charge was unrelated to his anti-war activities).

- The opposition politician Ilya Yashin was sentenced to eight and a half years in a general regime penal colony for spreading «fakes» about the Armed Forces.

- The musician and artist Sasha Skochilenko was sentenced to seven years in a general regime penal colony for spreading «fakes» about the Armed Forces.

- Alsu Kurmasheva, a journalist of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, was sentenced to six years in a general regime penal colony for spreading «fakes» about the Armed Forces. She was also under investigation for failing to comply with «foreign agent» requirements in connection with her collecting information on military activities.

- Oleg Orlov, co-chair of the Memorial Human Rights Center, was sentenced to two and a half years in a general regime penal colony for «repeatedly discrediting» the Armed Forces.

Additionally, three of the released individuals had been prosecuted in cases connected to the war in one way or another:

- Evan Gershkovich, a journalist of The Wall Street Journal, was sentenced to 16 years in a strict regime colony on charges of espionage. According to the investigation, he had been gathering information about a Russian defence enterprise.